Saving Stories in the Press

Author Talk with Chris Wisniewski

Falmouth Historical Society

September 12, 2024, 4:00 pm

Chris Wisniewski is an author and Personal Historian based in Wellfleet, Mass. She is the owner of a business called Saving Stories that helps individuals, families, and businesses preserve their history.

Photo: waves against seawall in Woods Hole, credit NOAA.

On September 21, 2023, the 85th anniversary of the Hurricane of 1938, this piece I wrote below commemorating the storm appeared in both The Norwich Bulletin and The Provincetown Independent - each slightly edited to focus on the local areas.

In Memory of the Storm of ’38

Today marks the 85th anniversary of the Hurricane of 1938. It was a storm that followed a path hurricanes were not supposed to travel. Arriving in an area where hurricanes, up to the point, were not supposed to happen. Hurricanes had been storms of the Caribbean and Florida. They were storms that veered out to sea at the Carolinas. Hurricanes did not happen here.

And yet, it came, speeding up the east coast like an express train. Knocking out communications along the way. Preventing any advance warning. It came, making landfall in Long Island a little after noon. It came, hitting southern Connecticut a few hours later with a force unprecedented. It came, downing huge elms and chestnut trees, leaving the streets a twist of wires swaying to and fro. It came, blasting with a 121 mph wind that you could not walk through, a wind you needed to shout above to be heard. It came, with a wind that gusted up to 186 mph. A wind that crumbled buildings like cardboard boxes. A wind that left the streets a mass of twisted sheet metal, strands of electrical wires, crushed automobiles, roof slates, broken glass, fallen shop signs, and shattered church steeples. It left streets impassable, except by climbing over and under, under and over the huge trunks and limbs of trees, their massive roots reaching up to the darkened skies above. It flooded bridges or washed them completely away. It left factory floors exposed to the elements, their roofs torn away, their contents soaked — destroyed. It toppled barns into fields, lifted chicken coops into the air and threw them into trees, with their residents still inside — squawking.

The storm blew for several hours, stopped briefly, and then blew again as the second half wailed over New England raking over what was left standing from before.

When the storm subsided, and it finally seemed safe, those who chose to venture out were met with the tidal surge. But this was not just any storm surge at a high tide. This was a storm surge on top of an astronomical tide of the autumnal equinox. A tide that measured between 17 to 25 feet from southern Connecticut up to Gloucester, Mass. A tide that rolled in waves that were recorded at 50 feet high, although, according to some witnesses, perhaps up to 80 feet tall. A tide that flooded cities that sat 40 miles inland with water that raced up swollen rivers. A tide whose waves washed boats far onto shore and left them beached on the main streets of cities. A tide that left huge tankers perched on railroad tracks and left shipyards crushed in a tangle of masts, and lines, and hulls. A tide that washed beaches clean of sand, of pavilions, of ice cream stands and clam shacks, of beach cottages, of entire seaside communities, and of the people who tried to ride out the storm.

The storm of '38 is still considered the most destructive hurricane in the recorded history of New England. It necessitated the creation of 50 CCC camps to clear all the downed timber over the next three years. It reshaped beaches from New York to Massachusetts. It decimated the the New England fishing fleet, destroying at least 2,600 vessels and damaging perhaps 3,370 more. It covered downtown Providence in 20 feet of water and covered the streets of Provincetown in 3 feet of sand. It extinguished Provincetown Light. It tore the large dragger Stella from her moorings in Provincetown and carried her ashore, settling her in the backyard of the Arctic explorer Commander Donald B. McMillan. It isolated Cape Cod from outside communications, forcing the Orleans cable station to relay messages from worried relatives off Cape to those here by routing them by cable from New York to Brest, France, and then back under the Atlantic Ocean to Orleans. It injured more than 1,700 people throughout New England. It killed at least 564 individuals, mostly along the shore.

Each year, the memory of this storm fades a little deeper into our community memory. Today on the 85th anniversary of the storm, as late September brings a quiet, heavy stillness to the air, let us pause in memory of the Hurricane of 1938.

Read online at The Norwich Bulletin, Norwich Conn., September 20, 2023

Read online at The Independent, Provincetown, Mass., September 21, 2023

Author Talk with Chris Wisniewski

Wellfleet Public Library

55 West Main Street,

Wellfleet, Mass. 02667

September 17, 2023, 7:00 pm

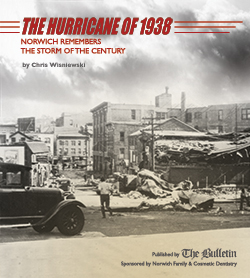

On the 85th anniversarry of the storm, Chris Wisniewski will talk about her book The Hurricane of 1938: Memories of the Storm of the Century. In 2013, Chris Wisniewski partnered with The Norwich Bulletin collecting personal accounts and orginal photographs from over 70 residents of Southeastern Conn. and Rhode Island. The ‘38 Hurricane still remains the most destructive storm in New England history. Come hear stories of how southern New England was permanently changed by the storm.

The Hurricane of 1938: The Science and The Stories

June 6, 2023

— Sold Out —

A museum talk and panel discussion at the Katherine Hepburn Cultural Arts Center in Old Saybrook, Conn.

Katharine

Hepburn's original family cottage in Old Saybrook was completely destroyed and washed away in the great huricanne 85 years ago as Katharine and her son stood nearby.

This panel discussion, "The Hurricane of 1938: The Science and The Stories," will explore the impact of the storm from inception to landfall with guest speakers: NBC 30 Chief Meteorologist Ryan Hanrahan, who will present the science of the storm and its path toward New England; Chris Wisniewski, author of The Hurricane of 1938: Memories of the Storm of the Century, who will share memories from survivors; and writer Tom Verde, who will tell of his own family’s tragic loss. Questions from the audience will be entertained following the presentations.

Personal Historians Northeast Network

blog post: November 2022

by Chris Wisniewski

THE OFFERING

The day before Halloween, my husband and I helped our daughter set up an ofrenda, an altar, in her apartment in Mexico City for Dia de Muertos, the day when Mexicans celebrate and remember family and friends who have passed.

We arranged vases of bright orange marigolds around a collection of photographs of people we have lost. Our daughter lit candles and heated charcoal to smolder copal, an incense made of tree resin that she had bought in the market. The scent of the marigolds and incense are believed to lead the dead back from the other side. We laid out small marzipan fruit; pan de muertos, a special sweet bread made for the dead; a tiny bottle of Tangeray for my father-in-law, who loved his martinis; for my mother, who had been so stylish, I added one of her pins; then we rounded out our offerings with a jackknife from my father, who had been able to fix anything except his cancer. When we were done and we sat back amid the glow of the candles, I could feel the presence of each of the people in the photographs. They felt closer to us — more present.

Creating an ofrenda is such a beautiful Mexican tradition — joyous and colorful, not somber. It is a way to welcome the dead back into our lives, to visually tell the story of a life, to keep their memory alive, to speak their name, to share their life. A time when the line between the living and the dead becomes more transparent.

It should be no surprise that a holiday dedicated to welcoming people from our past into our present resonates with me. After all, it is what much of my work as a Personal Historian is based on. However, I often wonder if the pull I have long felt towards Dia de Muertos had been seeded in me through a similar Polish tradition — even though it is one I have never experienced myself.

Whenever my mother told me the story of her mother, my babciu, coming to America, there was always one part of the telling that was the most significant. It wasn’t the long journey from her village in Poland to the port in Bremerhaven, Germany, nor the rough crossing in steerage class on the steamship, and it wasn’t the chaos of Ellis Island. It was the fact that my grandmother and her young daughter had arrived in New York on All Saints Day, a day when everyone in Poland returns to the graves of their families to gather together, clean tombstones, light candles, and share food and drink as they remember those who have passed. There, onboard her ship, looking out into the harbor of New York, all she felt was the breaking of that tradition of her family that stretched back for generations in her tiny hillside village in Poland, in the small cemetery where she knew all the names. She was aware that right then, on that day, everyone was gathering as they would for years to come — but now, she would no longer be part of the tradition. From that day on, it would continue, just without her…

I wish I had brought a photo of my grandmother for the ofrenda.

Today, I’m feeling the need to speak her name: Anna (née Garbacz) Banas.

The Hygienic Art Gallery presents an author talk with Chris Wisniewski

Saturday, September 10, 20225:00 PM

Join us on Saturday, September 10th from 5-6 PM for an evening of local history with Author Chris Wisniewski at the Hygienic Art Gallery on Bank Street in New London, as she reads from her book, "The Hurricane of 1938."

In September 1938, a massive hurricane with winds up to 120 mph roared into New England without warning. It washed away entire seaside communities at Watch Hill, Misquamicut, and at Ocean Beach in New London. In the middle of the storm, Bank Street in New London caught on fire while nearby large ships were tossed up on the railroad tracks by the wind and waves of the storm surge that raced up the Thames River. Within a few hours, the whole area was devastated.

In 2013, Chris Wisniewski partnered with The Norwich Bulletin on a book, The Hurricane of 1938: Memories of the Storm of the Century. It features personal accounts from over 65 residents of Southeastern Conn. and over 60 photographs, many never published before. The ‘38 Hurricane still remains the most destructive storm in New England history. Now, on the 84th anniversary of the hurricane, come hear stories of how southern New England was permanently changed by the storm.

Location: 79 Bank Street, New London, Conn. 06320

Bank Square Books presents an author talk and Q&A with Chris Wisniewski

May 18, 2022, 6:00pmChris Wisniewski will discuss her book, The Hurricane of 1938: Memories of the Storm of the Century.

Bank Square Books 53 West Main St., Mystic, Conn., 06355 tel: 860-536-3795

Interview on The Point with Mindy Todd

on WCAI, Local NPR for the Cape, Coast & Islands

Published April 25, 2022Aylette Jenness is a writer, photographer, and adventurer living on Cape Cod. She looks back at her life to find insight into the past as she is losing her physical sight due to macular degeneration. Her new book is Sometime a Clear Light: A Photographer's Journey Through Alaska, Nigeria, and Life. Mindy Todd hosts. Editor Chris Wisniewski and designer Andrea Pluhar join the conversation to discussion the collabloration in producing this book due to Aylette's failing eyesight. Listen to the whole interview here.

A Covid Anniversary Gift

After a year of distancing, what did I have to offer friends?

The Provincetown Independent, March 10, 2021

We’re coming up on a year, now — a year of confusion, isolation, sadness, and readjustment. Anniversaries are a time of reflection. What does this one mean?

There has been progress. Better mass adherence with the protocols needed to prevent the spread of this virus, national leadership that actually believes in science, vaccines rolling out slowly, bit by bit, jab by jab. But what else?

We have gone through this year with the ups and downs of trying to find new ways to connect with those we care about — Zoom cocktails, cold walks on the beach, outdoor gatherings heated by the closeness of friends, propane heaters, electric blankets, and the warmest coats we own; followed by Zoom exhaustion, seclusion, hibernation, a pulling in and away from the social connections we all long for and need.

Over these past few cold winter months, I found my own days of hibernation had begun to morph into a shapeless haze, while my feelings have fluctuated from low to very low to flat neutral, mixed with periods of deep gratitude for what I do have: for the beauty of the Outer Cape around me, and for all I did pack into my life back when I could.

Just recently, I began to feel the need for more structure in my life again. I wanted to start organizing my days better, to focus on more than just work and sleep and drink. I decided to force myself out of my own isolation and to reach out to friends with whom I hadn’t spoken in months.

But I was weary. What did I have to offer others now? After a year of distancing, it can seem easier just to be alone, to not bother others with our sadness or boredom. What is there to talk about anyway? What new have any of us done lately? The things our conversations used to revolve around — vacations, new adventures, parties, concerts, chance encounters with friends — are all gone. Would a call from me now be a gift or a burden? I wasn’t sure.

Slowly, I began making calls. With each one, I learned that many people are feeling the same — lonely, bored, isolated. Then, as our conversations went on, more was revealed: one friend has spent days unable to get out of bed; another has spent nights alone going over and over events in his life that he regrets. One outgoing friend starts our conversation by saying, “I may be quieter than normal. I feel I don’t have as much to say anymore.” One is worried that her steady music gig, her livelihood, which was suspended last spring, may never resume. Another lies in bed sleepless, worrying about an elderly mother who lives alone.

I have always loved making connections with strangers. Now, I often don’t make eye contact with others when I’m out. It’s as if wearing a mask makes us all invisible as individuals. I’m afraid I’m forgetting how to socialize. I’m often startled in a store if someone says something to me that pulls me out of my introspection and makes me feel normal, if only for a moment.

As I listen to these friends, I recognize that these admissions mark a sad chapter in our lives. Yet, somehow, hearing others express the same sense of isolation and social contraction, paradoxically, feels expansive. I am not alone in my aloneness. You are not alone in your aloneness. Briefly, we are alone together. That is a gift we can safely share with others right now.

Christine Wisniewski lives in Wellfleet and works as a personal historian at Saving Stories.

read the original article in the Provincetown Independent here.

WRITER’S LIFE:

How to Write a Story

That Lands in People’s Hearts

The Provincetown Independent, January 21, 2021 For writers, critique and compassion are two essential chapters.

...There are those for whom sharing, listening, absorbing criticism, and rewriting just don’t inspire hope. Writing is not for everyone. That’s why, after turning her own family’s stories into a book a decade ago, Wellfleet writer and historian Chris Wisniewski founded a personal history service. Wisniewski says she has always enjoyed hearing other people’s stories. She sits down with clients and lets them tell their own stories. Recording their voices, she says, is part of the process. “Everyone has their own style of speaking,” she says. “My goal is that the voice of the person I am interviewing comes through in the writing.” Working with families can be fascinating, and it is part of what makes the books Wisniewski collaborates on different from individuals’ memoirs. “Everybody remembers events in their own way,” she says. “As family members go back and forth with their memories, they create an interwoven memory together.”nWisniewski considers her work a privilege. “When people trust me with their stories and let me into their lives, I hold these stories sacred and it means so much to me to save them for future generations,” she says.

read the whole article here

LOS MUERTOS: An Ofrenda to All Souls

What if everyone were to light a candle?The Provincetown Independent, November 5, 2020

by Christine Wisniewski

This past week, as the days began to shorten and the nights became cooler, my thoughts drifted to All Souls Day, Dia de los Muertos. I have been trying to imagine what it would be like if everyone in this country, or around the world, were to light a candle and make an ofrenda to honor those who have died this year.

How many flowers would be cut? How many bottles of tequila/bourbon/wine/beer would be offered? How many candles would be lit? How many tears would be shed? As of this morning, 1,192,644 people in the world have died of Covid. There have been 230,522 deaths due to Covid in the United States alone. I’m afraid if we all honored the dead this year, we would set the world on fire, and I doubt our collective tears could douse the flames.

And what else are we mourning right now, in addition to those souls who have been lost to us? We mourn the loss of times spent with others, of being able to socialize freely, of the sensation of being wrapped in a friend’s embrace, of casual kisses on the cheek, and of the smiles of strangers we pass on the street. We mourn the loss of candlelit dinners inside with a circle of friends, the loss of live theater and music, of the ability to travel, and of the chance to plan holidays and celebrations with family and friends. We mourn the loss of our freedom to dance, to laugh, or to sing together, or to simply be in a crowded room, feeling the pulse of other humans around us. We mourn the loss of living without fear. There is so much to mourn this year — perhaps 2020 should be known as el Año de los Muertos.

So here we are at the turn of the season. Usually, I love autumn and the day-by-day cool down to winter. It’s a time to hunker down, pull out warm sweaters, make pots of simmering soup, stack firewood, and turn my thoughts inward, but this year is, of course, very different. As the nights have grown colder, I have been bringing in the plants from my deck. This year I am aware that this simple annual task is the signal that our outdoor socializing is coming to an end. Those sweet summer dinners with friends, lingering into the night with glasses of wine, playing music together and letting our voices rise up to the stars. With each plant I bring in, I mourn the loss of my connection to others and I worry about the line of winter nights that stretch out before us.

Only a few pots remain outside now, the last hearty plants. And of the flowers, what is left? Pots of marigolds, the traditional Mexican Flores de los Muertos. Tonight, on this night of All Souls Day, I light a candle beside my marigolds, and I pray that their scent will guide our journey through the coming winter and help us find peace over the long, cold, dark months of isolation to come.

Christine Wisniewski lives in Wellfleet and works as a personal historian at Saving Stories.